Lev Vygotsky: Thought and Language

Overview

Lev Vygotsky studied developmental psychology in Soviet Russia, approaching psychology from a peculiar perspective that differed from both western scholars and his Soviet contemporaries. Vygotsky approached psychology from an almost linguistic lens and attempted to reconcile problems that he found lacking in the approaches of other psychologists. Piaget is Vygotsky’s favorite whipping boy, and much of the work is aimed at critiquing Piaget’s work, which was the widely accepted western standard. In Thought and Language, Vygotsky looks at the process of learning language in human development as being directly related to thought and consciousness. Notably, he claims that the autistic speech of the toddler evolves to become the inner speech of the adult.

Notes

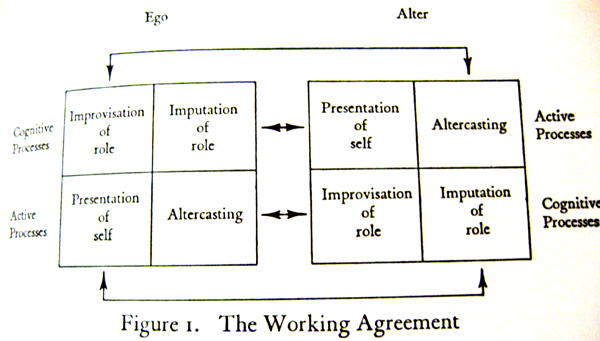

Psychology is the focus: Human function vs natural or biological. The focus is on the subject, not on the theory. Vygotsky’s approach is heavily influenced by Hegel. (p. xv) Vygotsky places importance on the distinction between conscious and unconscious action, which separates him from behaviorism. (p. xvi) The challenge of consciousness: Cannot define or explain consciousness in terms of itself! Cyclical pattern is a failing of theory. Social behavior relates to consciousness. “The mechanism of social behavior and the mechanism of consciousness are the same…. We are aware of ourselves, for we are aware of others, and in the same way as we know others; and this is as it is because in relation to ourselves we are in the same [position] as others are to us.” [Lev Vygotsky, “Consciousness as a problem of Psychology of behavior,” Soviet Psychology, 1979, 17:29-30]. Connection with George Mead: Mead’s struggle with behaviorism and Vygotsky’s struggle with consciousness are similar. (p. xxiv) The idea of context is the point of contention between Vygotsky and his Soviet contemporaries, especially Zinchenko. There is conflict over semiotics and role of history. (p. xlviii)

In author’s preface: speech and inner speech are a gallery to thought, as a new theory of consciousness. (p. lxi)

Vygotsky critiques methods of analysis: elemental psychology, deconstructs psyche into elements. This approach is flawed like only looking at elements in the periodic table in chemistry (as opposed to their interaction with each other) Sounds like a conflict between unit and system, interaction and independence. (p. 4) Looking at Gestalt psychology and association psychology. Major claim: Words are generalizations: connection of language and thought. Meaning making is an act of though. Communication is a spread of affect. Communication spreads and shares feelings and sensations, a frightened goose does not tell its flock what it has seen, but spreads its fear. (p. 6-7)

Criticism of Piaget: Refusal to apply theory to evidence in effort to preserve empiricality. This leads to facts that cannot be disentangled from philosophy. (p. 15) Vygotsky begins exploring autistic thought: Autism is egocentrism. Compare with Freud and the pleasure/reality principles as difference of autistic thought and realistic thought: Desires and satisfactions. (p. 18) Egocentric speech transforms into “inner speech”, which is highly important in later intellectual development. Practically, as communicative speech, ecocentric is useless, it does not communicate, but echoes itself like a chant. (p. 33)

Speech in developing children: Communication is bodily, much more than purely verbal. Specifically looking at toddlers, words strongly accompanied by gestures, etc. (p. 65) Thought, language and speech: The development of inner speech relates to development of social speech, which is a social means of thought. (p. 95)

Studying development of concepts. Take on category: Word denotes a collection, rather than individual concept. Several things arise: Complex, category, concept. (p. 115) Collections are grouped as “diffuse complexes”. Also arise pseudoconcepts, lies between a complex and a real concept. It is like a concept, but lacks the underlying ideas that define concepts as being more than just collections. (p. 119) The conceptual approach is what GOFAI projects tend to echo, but seem to miss the complex phase that must precede it.

Theories of learning scientific concepts: Interesting due to procedural model/simulation style of thought/reasoning. Some schools of thought believe that scientific concepts have no inward history, that they do not undergo development, but are absorbed via understanding and assimilation. Vygotsky claims that when new words are learned, they are seen as primitive generalizations, and then become replaced by higher types of generalizations. Scientific concepts specifically abide by a functional nature. This seems to echo comprehension of metaphors! (p. 149) Interesting note in childhood development: Failure to understand relations. Connections and relations between concepts arise gradually. Piaget cites Claparede’s law of awareness to explain establishment of relations: Awareness of difference precedes awareness of likeness (!). Connect with analogy, proves analogy is higher stage of development. (p. 163)

Types of understanding: personal/experiential vs schematic/scientific. Some concepts are spontaneously learned, derive from experience, but do not abide by shematic rules. Scientific concepts are learned as schematics, but do not connect to experience. “One might say that the development of the child’s spontaneous concepts proceeds upward, and the development of his scientific concepts downward, to a more elementary and concrete level.” So, spontaneous concepts gradually become generalized, while scientific concepts gradually become concrete. (p. 193) A critique of Gestalt psychology: cannot just use association. Must understand development of concepts as neither associative nor structural, but based on the relations of generality. This flows to the idea of productive thinking (Max Wertheimer), this involves analogy and generalizations of concepts on high order. (p. 204)

Vygotsky distinguishes analysis by elements to analysis by units. Units are capable of retaining and expressing the essence of the whole, as opposed to elements which are intrinsically fragmentary. The essence of word meaning, which develops over time, develops based on the thinker-knower, whose knowledge changes. Association theory is inadequate to account for these larger background changes. (p. 211-213)

“Inner speech is not the interior aspect of external speech–it is a function in itself. It still remains speech, i.e., thougth connected with words. But while in external speech thoguht is embodied in words, in inner speech words die as they bring forth thought. Inner speech is to a large extend thinking in pure meanings. It is a dynamic, shifting, unstable thing, fluttering between word and thought, the two more or less stable, more or less firmly dileneated components of verbal thought. Its true nature and place can be understood only after examining the next plane of verbal thought, the one still more inward than inner speech.” The plane of thought is a space of thinking which transcends thought and speech. Concepts formed here may not have expression in language. (p. 249) Speech and thought are manifestations of motivation, are connected to various theories of motivation. Compare with Maslow, The Sims, Facade, etc. (p. 252)

| Author/Editor | Vygotsky, Lev |

| Title | Thought and Language |

| Type | book |

| Context | |

| Tags | specials, media theory, linguistics, psychology |

| Lookup | Google Scholar, Google Books, Amazon |